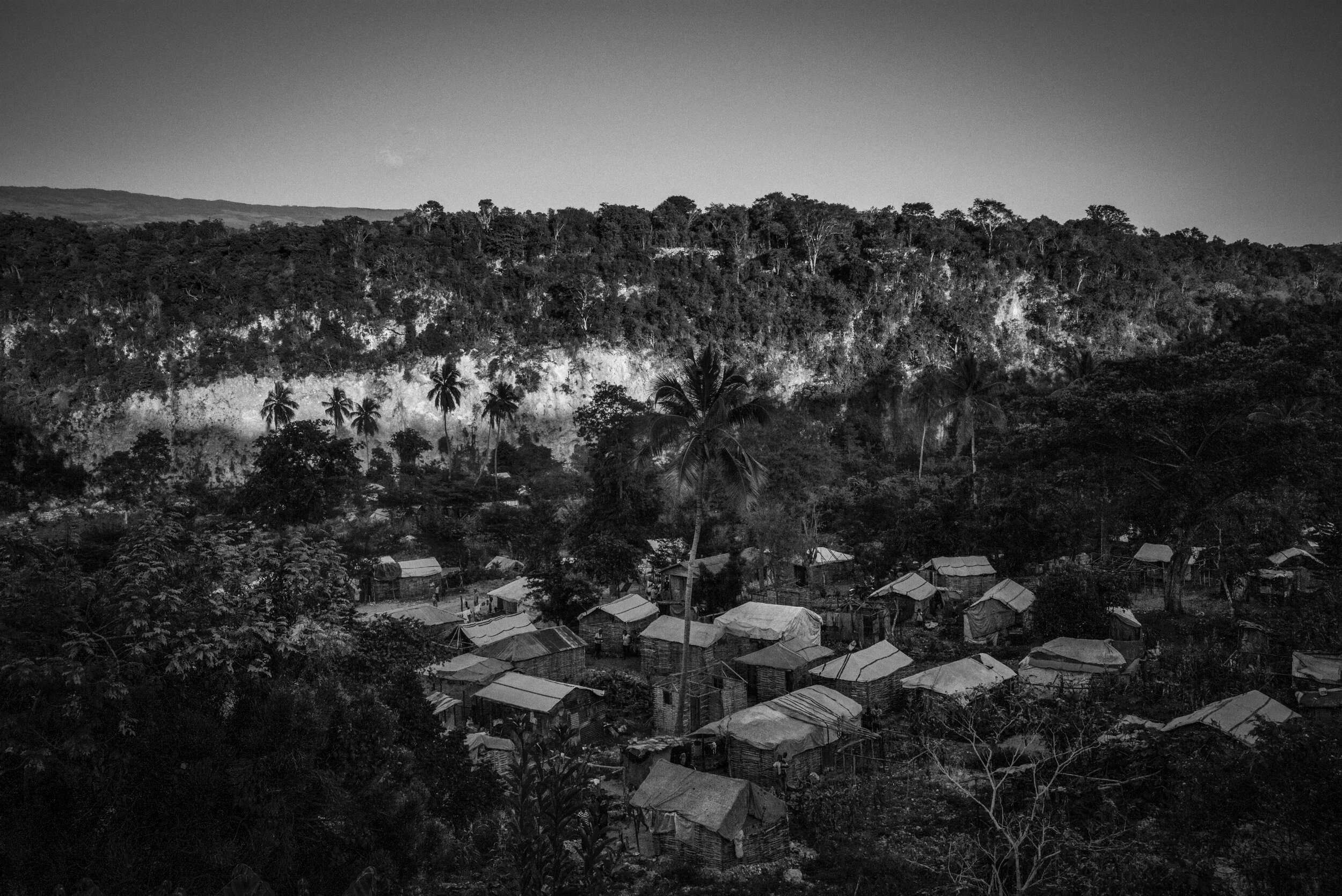

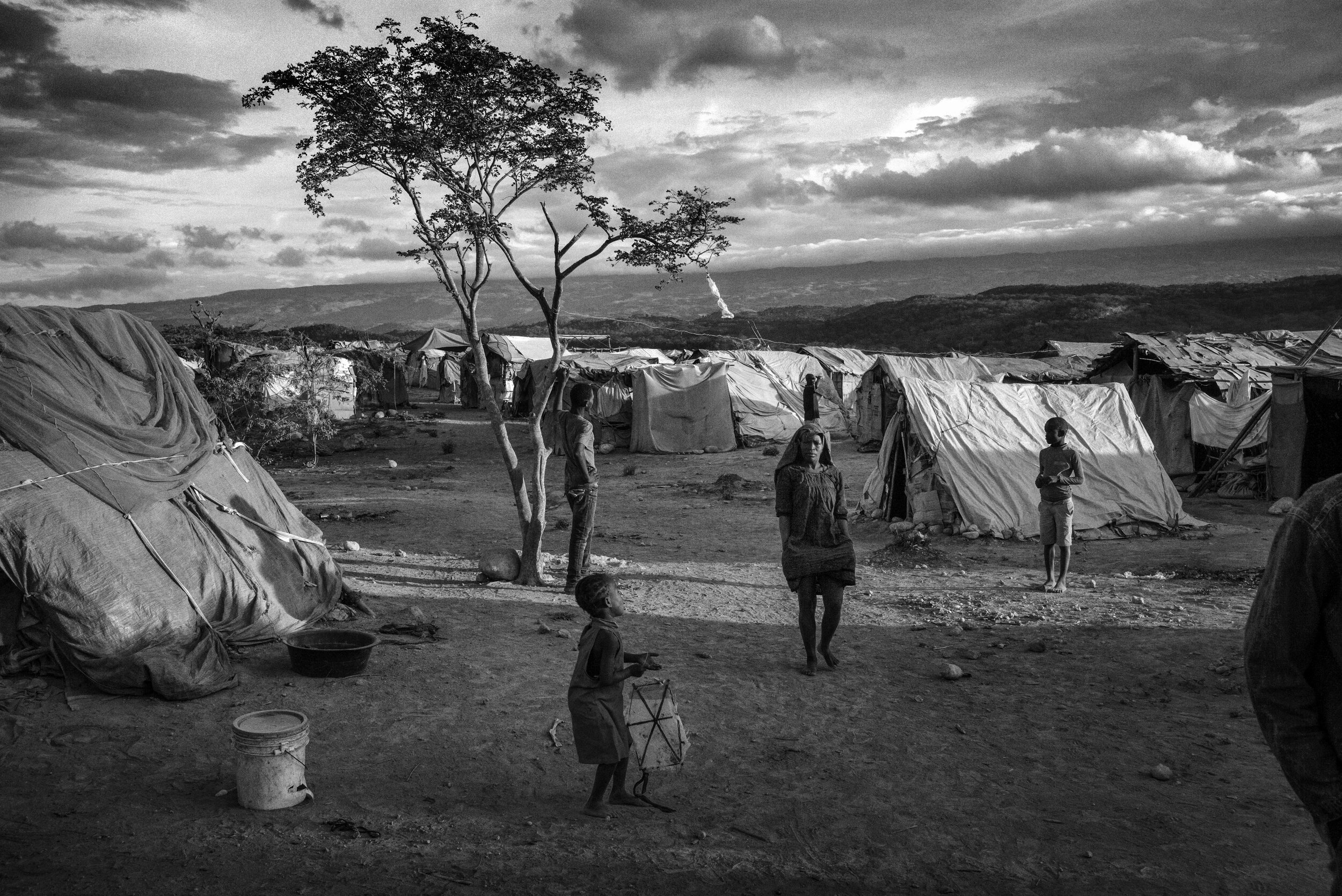

In Exile: along the border of The Dominican Republic

Photographs and Video by Patrick Witty

*These photos and videos originally appeared in The New York Times Magazine in January 2016.

Deportations and violence have driven tens of thousands of people of Haitian descent from their homes in the Dominican Republic. Thousands have ended up in makeshift camps along the border of the Dominican Republic. Renowned journalist and author Jonathan Katz and I traveled there in November 2015, for The New York Times Magazine. You can read more of Jonathan’s great work on his website.

The interview, condensed for space, was taken from the August/September 2016 edition of LFI Magazine.

LFI: What prompted you to dedicate yourself to a photography project around displacement?

PW: Throughout my career at The New York Times and TIME, I dealt with thousands and thousands of photographs of conflict, war and violence, all the dreadful things human beings do to each other. This certainly was the reason why, after I left WIRED last July (2005), I pursued the refugee crisis. In some ways my entire career and life led up to that moment. I oversaw our photographic coverage of the war in Afghanistan and Iraq for The New York Times and the Arab Spring for TIME - all of which contributed to the refugee crisis.

I’ve edited and published thousands of photos by so many gifted photographers who have dedicated their lives to telling these stories. It was an honor to do so, a duty I think. So, in August of last year (2015) when Kira Pollack, the Director of Photography at TIME (now the Creative Director at Vanity Fair), asked if I would go to Hungary to report on the refugee crisis and how smartphones are shaping their journeys, I couldn’t resist. I traveled to Hungary for TIME, then Croatia and Serbia, then Greece. It changed my life. I felt as if I was in the right place at the right time.

LFI: And yet the topics of refugees traveling from Syria was already being highly documented. Would you say that your long experience as a picture editor helped you to approach the situation from a different angle?

PW: As with most stories, the refugee crisis rises and falls in the news cycle with few places truly dedicated to continuing to tell the story the way it should be told. People, particularly Americans, need to be reminded on a daily basis of what is happening. That second question is really interesting. My goal in making pictures of the refugee crisis was very distinct and particular. And I think this came from my experience as a photo editor. The last thing I wanted to do was contribute to the noise. To make and publish pictures in ways similar to everyone else.

That’s why I took a different approach by publishing directly on social media. Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter became my platforms and I think the people who followed those feeds could feel a bit what it was like to be there. I was making pictures with one iPhone and streaming live with another iPhone as refugees were landing on the beach in Lesbos. My goal was never print, never permanence, but experience. Atmosphere.

I can think of so many photographers who were recording similar scenes, but each one has a particular voice. And the over-arching voice- that of the story, of the refugees and their plight - can always be heard. Of course, anyone can go to Lesbos and photograph refugees arriving. But how are you going to do this differently? Why you? Why now? This is an important question photographers need to ask themselves. And if you don’t have a good answer, then you’re getting in the way.

LFI: Did you find your answer when you were asked to visit Parc Cadeau?

PW: I was thankful for the opportunity. And particularly thankful to tell a story that very few others were telling. The situation was widely ignored and needed to be told.

LFI: How did you first approach the situation, and how did you feel?

PW: It’s always difficult in the beginning. A white American journalist appearing out of nowhere, walking around with a camera, isn’t easily ignored and I completely understand and appreciate their apprehension. After an hour or two, they knew I wasn’t a tourist and was there to tell their story. Jonathan Katz and I were the only journalists there. The people in the camps were certainly not used to the coverage. Their situation was horrific. Very poor conditions with the potential to be deadly on a very wide scale should the cholera spread. No toilets, no clean water, a constant layer of dust in the air.

LFI: How can a perfect image composition still be of importance under such horrible circumstances?

PW: It’s precisely under these circumstances that it has to be perfect. Life is unfolding in front of you and, as horrific as it may be, I’m there to make photographs that will resonate. Composition is a tool for that. If I were a doctor or an engineer, I’d be helping in other ways. I’m just a photographer and making pictures is how I’m trying to help.